In Part 1 of this series, we explored the rise of professional anthropology under the leadership of Franz Boas, a Jewish immigrant born in Minden, Germany, in 1858, who emigrated to the United States in 1887. Boas founded the anthropology program at Columbia University in 1899, which stood out for its inclusivity, admitting women and minorities from diverse backgrounds. This groundbreaking approach nurtured renowned figures such as Ruth Benedict, Margaret Mead, Zora Neale Hurston, Edward Sapir, Alfred Kroeber, Elsie Clews Parsons, Ruth Underhill, and Bertha P. Dutton. Among the remarkable anthropologists who emerged from Boas’ program was Gladys Amanda Reichard, whose work and legacy we will delve into in Part 2.

Gladys Amanda Reichard (1893–1955)

Gladys Amanda Reichard (1893–1955) was a distinguished American anthropologist and linguist renowned for extensively studying Native American languages and cultures, particularly among the Navajo and Pueblo peoples. She was born on July 17, 1893, in Bangor, Pennsylvania, in a Quaker household of Pennsylvania Dutch heritage. After teaching in public schools for six years following high school, Reichard pursued higher education at Swarthmore College, earning her bachelor’s degree in classics in 1919 and a master’s degree in 1920.

Academic & Professional Journey

Reichard’s academic journey led her to Columbia University, where she followed the path of other notable women who studied under the mentorship of Franz Boas. Like Ruth Benedict and others, she had pursued degrees in the humanities, not the sciences, and yet was accepted into the anthropology doctoral program. Under Boas’s guidance, she conducted fieldwork on the Wiyot language in California, culminating in her 1925 doctoral dissertation, Wiyot Grammar and Texts thus entering the foray of the relatively new discipline of linguistic anthropology.

In 1923, Reichard began her tenure as an instructor in anthropology at Barnard College, an undergraduate women’s college affiliated with Columbia University. That same year, she initiated fieldwork among the Navajo, collaborating initially with anthropologist Pliny Earle Goddard, curator of ethnology for the American Museum of Natural History. Following Goddard’s passing in 1928, Reichard immersed herself in Navajo life, residing with Navajo families to gain a profound understanding of their language, culture, and daily practices. She became fluent in Navajo, a rare achievement significantly enriching her research. However, her Navajo language studies encountered significant challenges due to conflicts with contemporaries like Edward Sapir and his student Harry Hoijer. These disputes stemmed from methodological differences and professional rivalries that influenced the reception of her contributions.

Reichard’s ethnographic fieldwork with the Navajo produced several publications on the Navajo language. One of her most notable books was a product of her immersive fieldwork and close collaboration with Navajo speakers, the four-hundred page Navaho Grammar (1945), which offers a comprehensive overview of Navajo phonetics, morphology, and syntax. This book is particularly valued for its linguistic rigor and detailed analysis, showcasing Reichard’s deep understanding of the language’s complexity.

Academic Treachery

Reichard emphasized the intricate relationships between language, culture, religion, and art. She was attentive to language variation, often producing detailed phonetic transcriptions that captured individual speaker differences, an outgrowth of working intimately with native Navajo speakers. This method contrasted sharply with the emerging focus of Sapir and his followers, who prioritized historical reconstruction and structural analysis of languages, adhering strictly to the ‘phonemic principle’—the idea that languages have a set of distinct phonemes that should be the focus of analysis.

Reichard’s skepticism toward the phonemic approach made her impatient with Sapir’s meticulous attention to it. Consequently, her transcriptions, which reflected individual pronunciation variations, were criticized by Sapir and Hoijer as containing ‘errors.’ They used these perceived inaccuracies to question the credibility of her work, thereby diminishing its recognition within the academic community. Additionally, Reichard’s immersive fieldwork style, involving close collaboration with native speakers in their communities, differed from the more detached methodologies that some of her contemporaries favored. This hands-on approach, combined with her status as a woman operating in a male-dominated field, further contributed to professional tensions and the marginalization of her contributions during her time. I can testify to this marginalization that continues to the present day; I did my master’s research and thesis on the Navajo and eventually pursued more Navajo studies for my doctoral work, but I never encountered Reichard’s name or any references to her work in articles nor textbooks that I utilized for my college teaching.

Regarding this treachery from well-placed academic elites like Sapir and Hoijer, anthropologist Nancy Mattina (p. 416) writes:

Virtually all of Reichard’s linguistic publications were met during her lifetime with the roar of male disapproval. She refused to observe the absolute partitioning of form from meaning, of method from circumstance then in vogue and she paid with her reputation for her nonconformity. Hockett (1940) panned Reichard’s grammar of Coeur d’Alene. Harry Hoijer discredited Reichard’s work on Navajo for the better part of three decades, culminating in his splenetic review in IJAL of her four-hundred page Navaho Grammar which he declared ‘wholly inadequate’ and without value to modern linguistics (1953, p. 83).George Trager subsequently piled on, writing in his review of the same book for American Anthropologist that Reichard had wasted two decades and the precious funds of the American Ethnological Society on its publication (1953, p. 429).

Mattina (pp. 416–417) further reflects on the professional challenges Reichard faced:

Mary Haas asserted that her student Karl Teeter had been forced to write his dissertation on Wiyot from “an entirely clean slate” based on information from a single 80-year-old speaker because grammatical descriptions prior to 1930—including Reichard’s dissertation on Wiyot grammar (1925)—were “noncommensurate” with the structuralist “plane” Haas favored. Teeter himself told Falk that Reichard “had a poor ear for

phonetics” which made the hundreds of pages of fieldnotes, texts, and analyses of Wiyot she left to posterity at the University of California Berkeley “too inaccurate” and “unreliable” for use (Falk 1999, p. 143).

According to Falk (1999), “Sapir’s persistent, behind-the-scenes attempts to sabotage Reichard’s career until his death in 1939 were as much an outlet for his frustrations with Boas’ higher standards of evidence and methodological pluralism as they were an expression of his well-documented contempt for professional women” (as cited in Mattina, p. 417). Furthermore, Mattina (p. 417) asserts, “It might be argued that Sapir’s ‘my way or the highway’ approach to scholarship is his most pervasive legacy in the culture of American linguistics. The battles he and his students waged against responsible colleagues like Reichard continue to divide us counterproductively along lines of gender, age, cultural identity, and disciplinary approach.”

Dedication to the Navajo

Reichard’s devotion to the Navajo people is exemplified by her dedication to running a federally sponsored school where she collaborated with students to develop a practical orthography for the Navajo language and, for the first time, to teach Navajo speakers to write their native language. Her comprehensive two-volume work, Navaho Religion: A Study of Symbolism, published in 1950, offers an in-depth analysis of Navajo beliefs and rituals, highlighting her commitment to preserving and understanding indigenous cultures. Beyond her work with the Navajo, Reichard conducted research on the Coeur d’Alene language in Washington state during the late 1920s for the Handbook of American Indian Languages. Collaborating with native speakers, she contributed to documenting and preserving this language, further showcasing her versatility and dedication as a linguist and anthropologist.

Reichard’s desire to learn weaving and immerse herself fully in Navajo culture motivated her to live with a family in 1930, where she participated in daily life, including “trips to the trading post, tribal council meetings, curing ceremonies, and the deaths of family members” (Adams State University Library Catalog, n.d.). This intimate ethnographic experience culminated in the 1934 publication of Spider Woman: A Story of Navajo Weavers and Chanters, a groundbreaking work written at a time when “it was unusual for an anthropologist to live with a family and become intimately connected with women’s activities” (Adams State University Library Catalog, n.d.). Not only does the book explore the technical side of weaving, but it also describes the connection of rugs to ceremony and chanting, where Reichard “provides a detailed description of the various chants and their significance, as well as the role of the chanters in Navajo society” (Goodreads, n.d.). Another reviewer highlights that “this is also significant because it is a woman anthropologist exploring the world of Navajo women, their material and spiritual culture” (Sacred Texts, n.d.).

In 1951, Reichard was promoted to full professor at Barnard College. She made significant strides in a male-dominated field and mentored numerous women anthropologists. She remained at Barnard until her passing on July 25, 1955, in Flagstaff, Arizona. Her extensive collection of notes on Navajo ethnology and language is preserved at the Museum of Northern Arizona, serving as a valuable resource for ongoing research. Reichard’s pioneering work bridged linguistic and cultural anthropology, offering profound insights into the societies she studied. Her immersive fieldwork, linguistic expertise, and dedication to education have left an enduring legacy in anthropology, inspiring future generations to approach cultural studies with empathy, respect, and scholarly rigor.

Untimely Death

With only three years to retirement from Barnard College “where she had been the only tenured faculty member (and chair) in the department of Anthropology for over thirty years” (Mattina, p. 415), Reichard suffered two strokes and died on July 25, 1955 at the age of 62. She had been staying on the grounds of her beloved Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff where she was planning to build a home on Museum property for her pending retirement (Mattina, p. 415).

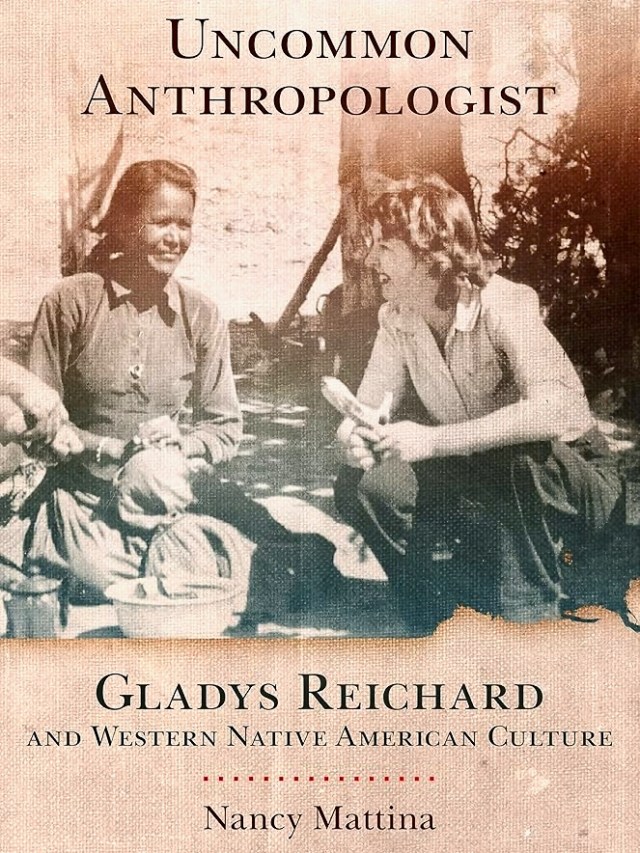

Reichard’s work has gained recognition in subsequent years for its depth and unique insights into the languages and cultures she studied. Her detailed documentation and holistic perspective are valuable resources in anthropology and linguistics. For a more comprehensive understanding of Reichard’s life and work, including her interactions with contemporaries like Sapir, Nancy Mattina’s biography, Uncommon Anthropologist: Gladys Reichard and Western Native American Culture, provides an in-depth exploration.

References & Resources

Adams State University Library Catalog. (n.d.). [Description of the book Spider Woman: A Story of Navajo Weavers and Chanters by G. A. Reichard]. Retrieved from https://adams.marmot.org/Record/.b1532476x

American Museum of Natural History. (n.d.). Retrieved December 30, 2024, from https://www.amnh.org

Barnard College. (n.d.). Retrieved December 26, 2024, from https://barnard.edu

Boas, F. (1911). Handbook of American Indian languages (Vol. 1). Government Printing Office. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/handbookofameric00boas/mode/2up

Falk, J. (1999). Women, language and linguistics: Three American stories from the first half of the 20th century. London: Routledge.

Golub, A. (Host). (2020, May 13). Uncommon anthropologist: Gladys Reichard and Western Native American culture [Audio interview with Nancy Mattina]. New Books Network. https://newbooksnetwork.com/nancy-mattina-uncommon-anthropologist-gladys-reichard-and-western-native-american-culture-u-oklahoma-press-2019

Goodreads. (n.d.). [Review of Spider Woman: A Story of Navajo Weavers and Chanters by G. A. Reichard]. Retrieved from https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/6543575-spider-woman

Goodreads. (n.d.). Books by Gladys A. Reichard. Retrieved December 31, 2024, from https://www.goodreads.com/author/list/30073.Gladys_A_Reichard

Lyon, W. H. (1987). Ednishodi Yazhe: The little priest and the understanding of Navajo culture. American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 11(1), 1–41. https://doi.org/10.17953/qt5bk898zn

Mattina, N. (2015). Gladys Reichard’s ear. In N. Weber, E. Guntly, Z. Lam, & S. Chen (Eds.), Papers for the International Conference on Salish and Neighbouring Languages 50 (University of British Columbia Working Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 40, pp. xx–xx). Retrieved from https://lingpapers.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2018/01/25-Mattina-Reichards-ear-08.pdf

Mattina, N. (2019). Uncommon anthropologist: Gladys Reichard and Western Native American culture. University of Oklahoma Press.

Museum of Northern Arizona. (n.d.). Retrieved December 29, 2024, from https://musnaz.org

Museum of Northern Arizona. (n.d.). Gladys A. Reichard collection (MS-22). Harold S. Colton Memorial Library. Retrieved December 31, 2024, from https://musnaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/MS-022_Reichard_RESTRICTED.pdf

PhilPapers. (n.d.). Women, language and linguistics: Three American stories from the first half of the 20th century by Julia S. Falk. Retrieved December 31, 2024, from https://philpapers.org/rec/FALWLA

Reichard, G. A. (1925). Wiyot grammar and texts. University of California Press.

Reichard, G.A. (1938). Coeur d’Alene. In, Franz Boas (Ed.), Handbook of

American Indian Languages 3, 517-707. New York: J.J. Augustin.

Reichard, G. A. (1997). Spider woman: A story of Navajo weavers and chanters (Standard ed.). University of New Mexico Press. (Original work published 1932)

Reichard, G. A. (2014). Navaho religion: A study of symbolism (Bollingen Series). Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1963)

Sacred Texts. (n.d.). [Review of Spider Woman: A Story of Navajo Weavers and Chanters by G. A. Reichard]. Retrieved from https://sacred-texts.com/nam/nav/sws/index.htm

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Gladys Reichard. In Wikipedia. Retrieved December 31, 2024, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gladys_Reichard

Images

Barnard Archives and Special Collections. (n.d.). Gladys Amanda Reichard [Photograph]. Retrieved December 23, 2024, from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Reichard_Anthro_ca35

University of Oklahoma Press. (n.d.). Cover image for “Uncommon Anthropologist: Gladys Reichard and Western Native American Culture” by Nancy Mattina [Image]. Retrieved December 23, 2024, from https://oklahoma-press-us.imgix.net/covers/9780806190075.jpg

Acknowledgements

Researched and written with the assistance of ChatGPT-4 by OpenAI (https://chat.openai.com)

Please Consider A Contribution To Help Maintain This Site!

`